Vanderbilt Monopoly to the Point That Laws Were Enacted to Keep His Practices From Happening Again

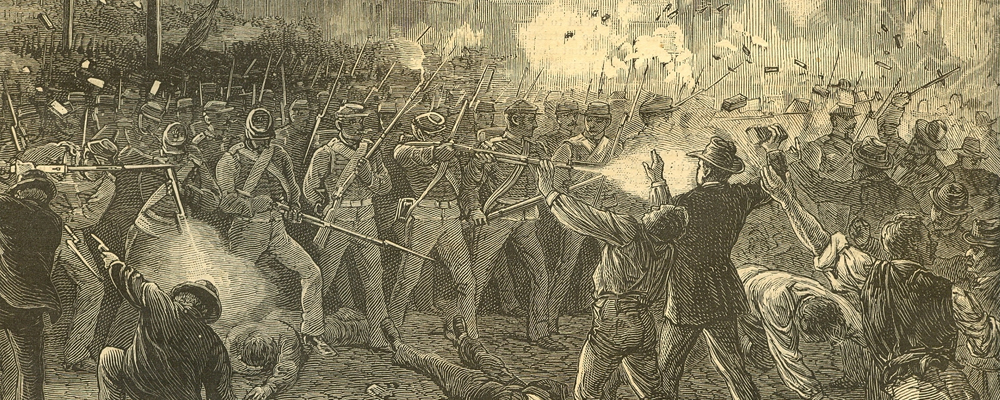

A Maryland National Guard unit fires upon strikers during the Bang-up Railroad Strike of 1877. Harper'south Weekly, via Wikimedia

The Slap-up Railroad Strike of 1877 heralded a new era of labor conflict in the United States. That year, mired in the brackish economy that followed the bursting of the railroads' financial bubble in 1873, rail lines slashed workers' wages (even, workers complained, every bit they reaped enormous government subsidies and paid shareholders lucrative stock dividends). Workers struck from Baltimore to St. Louis, shutting down railroad traffic—the nation's economic lifeblood—across the country.

Panicked concern leaders and friendly political officials reacted quickly. When local law forces would non or could not suppress the strikes, governors chosen out state militias to suspension them and restore rail service. Many strikers destroyed rails belongings rather than allow militias to reopen the rails. The protests approached a class war. The governor of Maryland deployed the land'south militia. In Baltimore, the militia fired into a crowd of striking workers, killing xi and wounding many more. Strikes convulsed towns and cities beyond Pennsylvania. The head of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Thomas Andrew Scott, suggested that if workers were unhappy with their wages, they should be given "a burglarize diet for a few days and come across how they like that kind of bread."1 Law enforcement in Pittsburgh refused to put downwards the protests, so the governor called out the state militia, who killed twenty strikers with bayonets and burglarize burn. A month of anarchy erupted. Strikers set up fire to the city, destroying dozens of buildings, over a hundred engines, and over a thousand cars. In Reading, strikers destroyed rail property and an aroused crowd bombarded militiamen with rocks and bottles. The militia fired into the crowd, killing ten. A general strike erupted in St. Louis, and strikers seized rail depots and declared for the eight-hour mean solar day and the abolition of child labor. Federal troops and vigilantes fought their fashion into the depot, killing 18 and breaking the strike. Rail lines were shut down all beyond neighboring Illinois, where coal miners struck in sympathy, tens of thousands gathered to protest under the aegis of the Workingmen'due south Party, and twenty protesters were killed in Chicago by special police and militiamen.

Courts, police, and state militias suppressed the strikes, but information technology was federal troops that finally defeated them. When Pennsylvania militiamen were unable to contain the strikes, federal troops stepped in. When militia in West Virginia refused to intermission the strike, federal troops bankrupt it instead. On the orders of the president, American soldiers were deployed all across northern rail lines. Soldiers moved from town to boondocks, suppressing protests and reopening rail lines. Half-dozen weeks after information technology had begun, the strike had been crushed. Nearly 100 Americans died in "The Great Upheaval." Workers destroyed nearly $40 1000000 worth of property. The strike galvanized the state. It convinced laborers of the need for institutionalized unions, persuaded businesses of the need for even greater political influence and government help, and foretold a half century of labor conflict in the United states.two

II. The March of Majuscule

John Pierpont Morgan with ii friends, ca.1907. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-92327

Growing labor unrest accompanied industrialization. The greatest strikes first hit the railroads only because no other industry had so finer marshaled together upper-case letter, government support, and bureaucratic direction. Many workers perceived their new powerlessness in the coming industrial order. Skills mattered less and less in an industrialized, mass-producing economy, and their strength every bit individuals seemed ever smaller and more insignificant when companies grew in size and power and managers grew flush with wealth and influence. Long hours, dangerous working conditions, and the difficulty of supporting a family unit on meager and unpredictable wages compelled armies of labor to organize and battle against the ability of capital.

The post–Civil War era saw revolutions in American industry. Technological innovations and national investments slashed the costs of production and distribution. New administrative frameworks sustained the weight of vast firms. National credit agencies eased the uncertainties surrounding rapid motion of capital amid investors, manufacturers, and retailers. Plummeting transportation and communication costs opened new national media, which advertising agencies used to nationalize various products.

By the turn of the century, corporate leaders and wealthy industrialists embraced the new principles of scientific management, or Taylorism, subsequently its noted proponent, Frederick Taylor. The precision of steel parts, the harnessing of electricity, the innovations of machine tools, and the mass markets wrought by the railroads offered new avenues for efficiency. To friction match the demands of the machine age, Taylor said, firms needed a scientific organization of production. He urged all manufacturers to increase efficiency by subdividing tasks. Rather than having xxx mechanics individually making thirty machines, for case, a manufacturer could assign thirty laborers to perform thirty singled-out tasks. Such a shift would non but make workers as interchangeable as the parts they were using, it would also dramatically speed up the procedure of production. If managed by trained experts, specific tasks could be done quicker and more than efficiently. Taylorism increased the scale and scope of manufacturing and immune for the flowering of mass product. Building on the use of interchangeable parts in Civil War–era weapons manufacturing, American firms advanced mass production techniques and technologies. Singer sewing machines, Chicago packers' "disassembly" lines, McCormick grain reapers, Duke cigarette rollers: all realized unprecedented efficiencies and achieved unheard-of levels of production that propelled their companies into the forefront of American business organization. Henry Ford fabricated the assembly line famous, allowing the production of automobiles to skyrocket every bit their cost plummeted, but various American firms had been paving the way for decades.3

Glazier Stove Company, moulding room, Chelsea, Michigan, ca1900-1910. Library of Congress, LC-D4-42785.

Cyrus McCormick had overseen the construction of mechanical reapers (used for harvesting wheat) for decades. He had relied on skilled blacksmiths, skilled machinists, and skilled woodworkers to handcraft horse-fatigued machines. But production was tiresome and the machines were expensive. The reapers still enabled massive efficiency gains in grain farming, but their loftier cost and slow product times put them out of reach of about American wheat farmers. But and then, in 1880, McCormick hired a product manager who had overseen the manufacturing of Colt firearms to transform his system of product. The Chicago institute introduced new jigs, steel gauges, and pattern machines that could brand precise duplicates of new, interchangeable parts. The company had produced twenty-one thousand machines in 1880. It fabricated twice as many in 1885, and past 1889, less than a decade later, it was producing over ane hundred thousand a year.4

Industrialization and mass production pushed the U.s.a. into the forefront of the world. The American economy had lagged behind Uk, Germany, and France equally recently as the 1860s, but past 1900 the United States was the world's leading manufacturing nation. Thirteen years later on, by 1913, the United States produced 1 tertiary of the world's industrial output—more than Uk, French republic, and Germany combined.five

Firms such as McCormick'due south realized massive economies of scale: after accounting for their initial massive investments in machines and marketing, each additional product lost the visitor relatively fiddling in product costs. The bigger the product, and so, the bigger the profits. New industrial companies therefore hungered for markets to keep their loftier-volume product facilities operating. Retailers and advertisers sustained the massive markets needed for mass production, and corporate bureaucracies meanwhile allowed for the management of giant new firms. A new grade of managers—comprising what 1 prominent economical historian chosen the "visible paw"—operated between the worlds of workers and owners and ensured the efficient operation and administration of mass product and mass distribution. Fifty-fifty more important to the growth and maintenance of these new companies, nonetheless, were the legal creations used to protect investors and sustain the power of massed capital.6

The costs of mass production were prohibitive for all but the very wealthiest individuals, and, even then, the risks would be too great to conduct individually. The corporation itself was ages sometime, but the actual correct to incorporate had by and large been reserved for public works projects or authorities-sponsored monopolies. Afterward the Civil War, however, the corporation, using new state incorporation laws passed during the Marketplace Revolution of the early nineteenth century, became a legal mechanism for near any enterprise to align vast amounts of capital while limiting the liability of shareholders. By washing their hands of legal and financial obligations while still retaining the right to profit massively, investors flooded corporations with the capital needed to industrialize.

Simply a competitive marketplace threatened the promise of investments. Once the efficiency gains of mass product were realized, profit margins could exist undone past cutthroat contest, which kept costs depression as price cutting sank into profits. Companies rose and fell—and investors suffered losses—as manufacturing firms struggled to maintain supremacy in their particular industries. Economies of scale were a double-edged sword: while additional production provided immense profits, the high fixed costs of operating expensive factories dictated that even modest losses from selling underpriced goods were preferable to not selling profitably priced goods at all. And every bit marketplace share was won and lost, profits proved unstable. American industrial firms tried everything to avoid competition: they formed informal pools and trusts, they entered price-fixing agreements, they divided markets, and, when blocked past antitrust laws and renegade price cutting, merged into consolidations. Rather than endure from ruinous competition, firms combined and bypassed information technology altogether.

Between 1895 and 1904, and peaking between 1898 and 1902, a moving ridge of mergers rocked the American economy. Competition melted away in what is known as "the great merger movement." In nine years, 4 1000 companies—nearly twenty percent of the American economy—were folded into rival firms. In near every major manufacture, newly consolidated firms such every bit Full general Electric and DuPont utterly dominated their market. 40-1 separate consolidations each controlled over 70 percentage of the market in their corresponding industries. In 1901, financier J. P. Morgan oversaw the formation of United States Steel, built from eight leading steel companies. Industrialization was built on steel, and 1 firm—the earth's get-go billion-dollar company—controlled the market. Monopoly had arrived.7

Iii. The Ascent of Inequality

Industrial capitalism realized the greatest advances in efficiency and productivity that the world had ever seen. Massive new companies marshaled capital on an unprecedented scale and provided enormous profits that created unheard-of fortunes. Merely it also created millions of low-paid, unskilled, unreliable jobs with long hours and dangerous working conditions. The notion of a glittering earth of wealth and technological innovation masking massive social inequities and deep-seated corruption gave the era its most common characterization, the Gilded Age, which drew from the title of an 1873 satirical novel written by Marking Twain and Charles Warner. Industrial commercialism confronted Golden Age Americans with unprecedented inequalities. The sudden appearance of the extreme wealth of industrial and financial leaders alongside the crippling squalor of the urban and rural poor shocked Americans. "This association of poverty with progress is the great enigma of our times," economist Henry George wrote in his 1879 bestseller, Progress and Poverty. viii

The great financial and industrial titans, the so-chosen robber barons, including railroad operators such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, oilmen such equally J. D. Rockefeller, steel magnates such as Andrew Carnegie, and bankers such as J. P. Morgan, won fortunes that, adjusted for inflation, are still amongst the largest the nation has ever seen. According to various measurements, in 1890 the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans owned ane fourth of the nation's assets; the top ten percent owned over lxx percentage. And inequality only accelerated. Past 1900, the richest 10 percentage controlled mayhap xc percentage of the nation's wealth.9

Every bit these vast and unprecedented new fortunes accumulated among a small number of wealthy Americans, new ideas arose to bestow moral legitimacy upon them. In 1859, British naturalist Charles Darwin published his theory of evolution through natural selection in his On the Origin of Species. It was not until the 1870s, however, that those theories gained widespread traction amid biologists, naturalists, and other scientists in the United States and, in plough, challenged the social, political, and religious beliefs of many Americans. One of Darwin'southward greatest popularizers, the British sociologist and biologist Herbert Spencer, applied Darwin's theories to gild and popularized the phrase survival of the fittest. The fittest, Spencer said, would demonstrate their superiority through economic success, while land welfare and private charity would lead to social degeneration—it would encourage the survival of the weak.10

Jacob A. Riis, "5 Cents a Spot," unauthorized immigration lodgings in a Bayard Street tenement, New York City, ca.1890. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-16348

"There must exist complete surrender to the law of natural option," the Baltimore Sun journalist H. L. Mencken wrote in 1907. "All growth must occur at the tiptop. The strong must grow stronger, and that they may do so, they must waste material no forcefulness in the vain task of trying to uplift the weak."eleven By the fourth dimension Mencken wrote those words, the ideas of social Darwinism had spread among wealthy Americans and their defenders. Social Darwinism identified a natural order that extended from the laws of the cosmos to the workings of industrial order. All species and all societies, including modern humans, the theory went, were governed by a relentless competitive struggle for survival. The inequality of outcomes was to be non just tolerated but encouraged and celebrated. It signified the progress of species and societies. Spencer's major work, Synthetic Philosophy, sold about iv hundred thousand copies in the United States by the time of his expiry in 1903. Gilded Historic period industrial elites, such as steel magnate Andrew Carnegie, inventor Thomas Edison, and Standard Oil'south John D. Rockefeller, were amongst Spencer's prominent followers. Other American thinkers, such as Yale's William Graham Sumner, echoed his ideas. Sumner said, "Earlier the tribunal of nature a man has no more right to life than a rattlesnake; he has no more correct to liberty than any wild animal; his right to pursuit of happiness is nothing just a license to maintain the struggle for existence."12

Merely not all so eagerly welcomed inequalities. The spectacular growth of the U.S. economic system and the ensuing inequalities in living conditions and incomes confounded many Americans. But as industrial commercialism overtook the nation, it accomplished political protections. Although both major political parties facilitated the ascension of big business and used state power to back up the interests of capital confronting labor, big business looked primarily to the Republican Party.

The Republican Political party had risen every bit an antislavery faction committed to "free labor," but information technology was also an ardent supporter of American business organization. Abraham Lincoln had been a corporate lawyer who dedicated railroads, and during the Civil State of war the Republican national government took advantage of the wartime absence of southern Democrats to button through a pro-business calendar. The Republican congress gave millions of acres and dollars to railroad companies. Republicans became the party of business, and they dominated American politics throughout the Gilded Age and the offset several decades of the twentieth century. Of the sixteen presidential elections between the Civil War and the Keen Depression, Republican candidates won all simply iv. Republicans controlled the Senate in xx-seven out of 30-two sessions in the same period. Republican authority maintained a high protective tariff, an import tax designed to shield American businesses from foreign competition. Southern planters had opposed this policy before the war simply at present could do nothing to stop it. It provided the protective foundation for a new American industrial social club, while Spencer'southward social Darwinism provided moral justification for national policies that minimized government interference in the economy for anything other than the protection and back up of business concern.

IV. The Labor Movement

Lawrence Textile Strike, 1912. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-23725.

The ideas of social Darwinism attracted lilliputian back up among the mass of American industrial laborers. American workers toiled in difficult jobs for long hours and little pay. Mechanization and mass production threw skilled laborers into unskilled positions. Industrial piece of work ebbed and flowed with the economy. The typical industrial laborer could wait to exist unemployed one month out of the year. They labored lx hours a calendar week and could still expect their almanac income to fall below the poverty line. Among the working poor, wives and children were forced into the labor market to compensate. Crowded cities, meanwhile, failed to accommodate growing urban populations and skyrocketing rents trapped families in crowded slums.

Strikes ruptured American manufacture throughout the late nineteenth and early on twentieth centuries. Workers seeking higher wages, shorter hours, and safer working weather condition had struck throughout the antebellum era, but organized unions were fleeting and transitory. The Civil War and Reconstruction seemed to briefly distract the nation from the plight of labor, only the finish of the sectional crisis and the explosive growth of big business organization, unprecedented fortunes, and a vast industrial workforce in the final quarter of the nineteenth century sparked the ascension of a vast American labor movement.

The failure of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 convinced workers of the need to organize. Marriage memberships began to climb. The Knights of Labor enjoyed considerable success in the early 1880s, due in office to its efforts to unite skilled and unskilled workers. Information technology welcomed all laborers, including women (the Knights only barred lawyers, bankers, and liquor dealers). By 1886, the Knights had over seven hundred grand members. The Knights envisioned a cooperative producer-centered social club that rewarded labor, non capital letter, but, despite their sweeping vision, the Knights focused on practical gains that could be won through the organization of workers into local unions.13

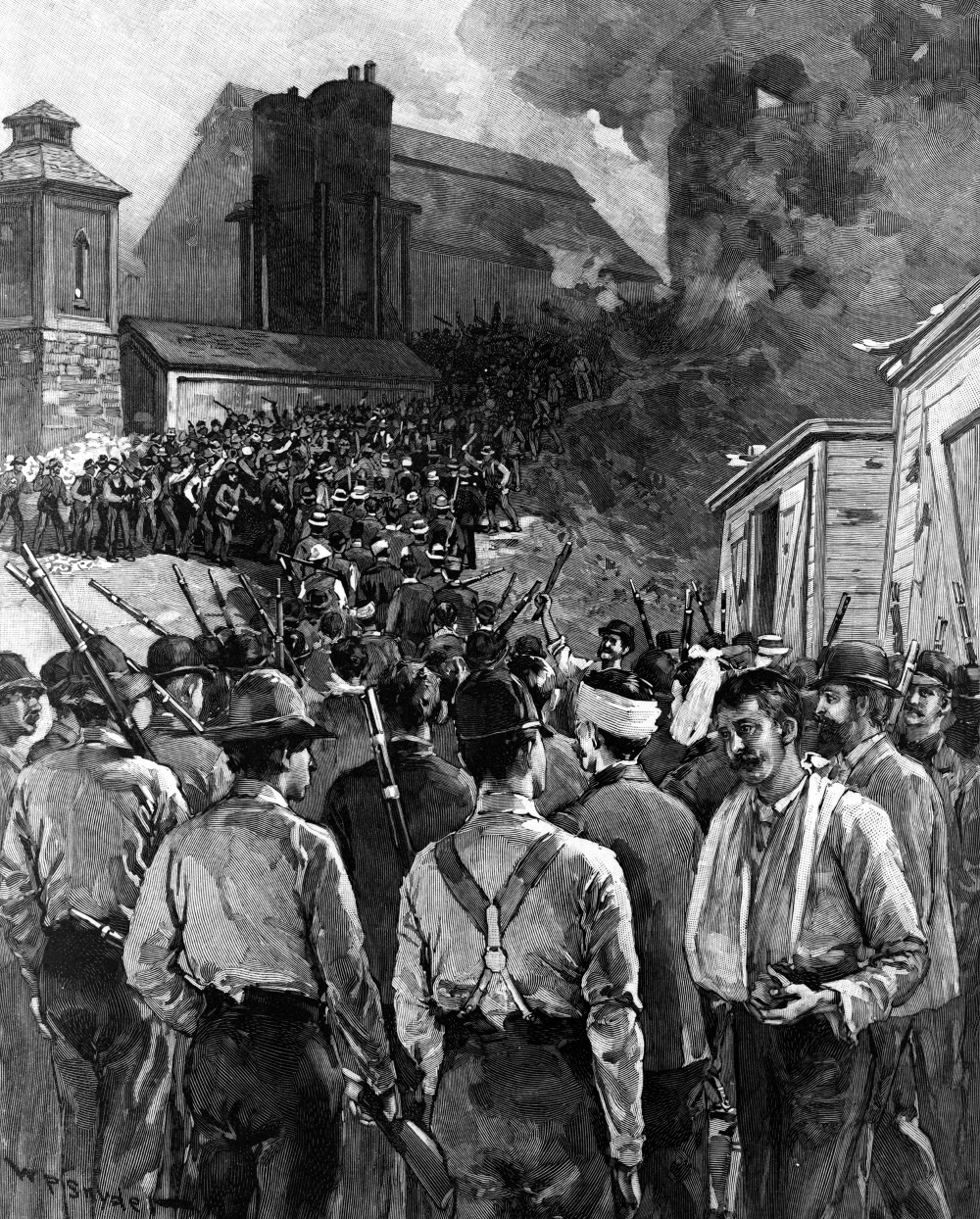

An 1892 encompass of Harper's Weekly depicting the Homestead Riot, showed Pinkerton men who had surrendered to the steel mill workers navigating a gauntlet of violent strikers. W.P. Snyder (artist) after a photograph by Dabbs, "The Homestead Anarchism," 1892. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-126046.

In Marshall, Texas, in the leap of 1886, one of Jay Gould's rail companies fired a Knights of Labor fellow member for attending a union coming together. His local union walked off the job, and soon others joined. From Texas and Arkansas into Missouri, Kansas, and Illinois, nearly ii hundred thousand workers struck against Gould's rail lines. Gould hired strikebreakers and the Pinkerton Detective Agency, a kind of private security contractor, to suppress the strikes and become the rails moving over again. Political leaders helped him, and country militias were chosen in back up of Gould's companies. The Texas governor chosen out the Texas Rangers. Workers countered by destroying belongings, only winning them negative headlines and for many justifying the use of strikebreakers and militiamen. The strike broke, briefly undermining the Knights of Labor, just the organization regrouped and gear up its optics on a national campaign for the eight-hour day.xiv

In the summer of 1886, the campaign for an viii-hour day, long a rallying cry that united American laborers, culminated in a national strike on May 1, 1886. Somewhere between 3 hundred thousand and 5 hundred thousand workers struck across the country.

In Chicago, police forces killed several workers while breaking up protesters at the McCormick reaper works. Labor leaders and radicals chosen for a protest at Haymarket Square the following twenty-four hour period, which police also proceeded to break up. But as they did, a bomb exploded and killed seven policemen. Police fired into the crowd, killing four. The deaths of the Chicago policemen sparked outrage beyond the nation, and the sensationalization of the Haymarket Riot helped many Americans to associate unionism with radicalism. Eight Chicago anarchists were arrested and, despite no direct prove implicating them in the bombing, were charged and found guilty of conspiracy. Four were hanged (and i died by suicide before he could be executed). Membership in the Knights had peaked earlier that year but barbarous rapidly afterward Haymarket; the group became associated with violence and radicalism. The national movement for an 8-hour mean solar day complanate.15

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) emerged as a conservative alternative to the vision of the Knights of Labor. An alliance of craft unions (unions equanimous of skilled workers), the AFL rejected the Knights' expansive vision of a "producerist" economy and advocated "pure and uncomplicated trade unionism," a plan that aimed for applied gains (higher wages, fewer hours, and safer conditions) through a bourgeois approach that tried to avert strikes. But workers continued to strike.

In 1892, the Confederate Association of Iron and Steel Workers struck at ane of Carnegie's steel mills in Homestead, Pennsylvania. After repeated wage cuts, workers shut the establish down and occupied the mill. The plant's operator, Henry Dirt Frick, immediately called in hundreds of Pinkerton detectives, but the steel workers fought back. The Pinkertons tried to land by river and were besieged by the hit steel workers. After several hours of pitched battle, the Pinkertons surrendered, ran a bloody gauntlet of workers, and were kicked out of the mill grounds. Simply the Pennsylvania governor called the state militia, broke the strike, and reopened the mill. The union was essentially destroyed in the aftermath.xvi

Notwithstanding, despite repeated failure, strikes connected to roll beyond the industrial landscape. In 1894, workers in George Pullman's Pullman car factories struck when he cut wages past a quarter but kept rents and utilities in his company town abiding. The American Railway Union (ARU), led past Eugene Debs, launched a sympathy strike: the ARU would pass up to handle any Pullman cars on any rail line anywhere in the country. Thousands of workers struck and national railroad traffic ground to a halt. Unlike in nearly every other major strike, the governor of Illinois sympathized with workers and refused to acceleration the country militia. It didn't matter. In July, President Grover Cleveland dispatched thousands of American soldiers to intermission the strike, and a federal court issued a preemptive injunction confronting Debs and the union's leadership. The strike violated the injunction, and Debs was arrested and imprisoned. The strike evaporated without its leadership. Jail radicalized Debs, proving to him that political and judicial leaders were but tools for capital in its struggle against labor.17 But information technology wasn't just Debs. In 1905, the degrading weather of industrial labor sparked strikes across the country. The final two decades of the nineteenth century saw over twenty thousand strikes and lockouts in the U.s.. Industrial laborers struggled to carve for themselves a piece of the prosperity lifting investors and a rapidly expanding center class into unprecedented standards of living. But workers were not the only ones struggling to stay afloat in industrial America. American farmers as well lashed out confronting the inequalities of the Gilded Historic period and denounced political corruption for enabling economical theft.

Two women strikers on picket line during the "Uprising of the 20,000", garment workers strike, New York Urban center, 1910. Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-49516 .

V. The Populist Movement

"Wall Street owns the country," the Populist leader Mary Elizabeth Lease told dispossessed farmers around 1890. "It is no longer a government of the people, past the people, and for the people, but a regime of Wall Street, past Wall Street, and for Wall Street." Farmers, who remained a bulk of the American population through the first decade of the twentieth century, were hitting specially hard by industrialization. The expanding markets and technological improvements that increased efficiency also decreased commodity prices. Commercialization of agriculture put farmers in the easily of bankers, railroads, and various economic intermediaries. Equally the decades passed, more than and more farmers fell ever farther into debt, lost their state, and were forced to enter the industrial workforce or, especially in the South, became landless farmworkers.

The rise of industrial giants reshaped the American countryside and the Americans who called it home. Railroad spur lines, telegraph lines, and credit crept into farming communities and linked rural Americans, who still fabricated up a majority of the country's population, with towns, regional cities, American fiscal centers in Chicago and New York, and, somewhen, London and the world's financial markets. Meanwhile, improved farm mechanism, piece of cake credit, and the latest consumer appurtenances flooded the countryside. Only new connections and new conveniences came at a toll.

Farmers had always been dependent on the whims of the weather and local markets. Just now they staked their financial security on a national economic organisation subject to rapid cost swings, rampant speculation, and limited regulation. Frustrated American farmers attempted to reshape the fundamental structures of the nation'south political and economic systems, systems they believed enriched parasitic bankers and industrial monopolists at the expense of the many laboring farmers who fed the nation by producing its many crops and subcontract goods. Their dissatisfaction with an erratic and impersonal system put many of them at the forefront of what would become mayhap the most serious challenge to the established political economic system of Gilt Age America. Farmers organized and launched their challenge beginning through the cooperatives of the Farmers' Alliance and later on through the politics of the People's (or Populist) Political party.

Mass production and business consolidations spawned giant corporations that monopolized well-nigh every sector of the U.S. economy in the decades after the Civil War. In contrast, the economic power of the individual farmer sank into oblivion. Threatened past ever-plummeting commodity prices and ever-rise indebtedness, Texas agrarians met in Lampasas, Texas, in 1877 and organized the starting time Farmers' Alliance to restore some economic power to farmers as they dealt with railroads, merchants, and bankers. If big business relied on its numerical force to exert its economic will, why shouldn't farmers unite to counter that ability? They could share mechanism, bargain from wholesalers, and negotiate college prices for their crops. Over the following years, organizers spread from town to boondocks across the former Confederacy, the Midwest, and the Nifty Plains, holding evangelical-style camp meetings, distributing pamphlets, and establishing over one thou alliance newspapers. Every bit the brotherhood spread, then likewise did its nearly-religious vision of the nation's future as a "cooperative commonwealth" that would protect the interests of the many from the predatory greed of the few. At its pinnacle, the Farmers' Alliance claimed 1,500,000 members coming together in twoscore,000 local sub-alliances.18

The banner of the showtime Texas Farmers' Alliance. Source: N. A. Dunning (ed.), Farmers' Alliance History and Agricultural Digest (Washington D.C.: Alliance Publishing Co., 1891), iv.

The alliance'south most innovative programs were a series of farmers' cooperatives that enabled farmers to negotiate higher prices for their crops and lower prices for the appurtenances they purchased. These cooperatives spread beyond the S betwixt 1886 and 1892 and claimed more than a 1000000 members at their loftier indicate. While most failed financially, these "philanthropic monopolies," as i alliance speaker termed them, inspired farmers to look to large-scale organization to cope with their economic difficulties.19 Simply cooperation was only office of the brotherhood message.

In the South, alliance-backed Democratic candidates won iv governorships and xl-eight congressional seats in 1890.20 Simply at a fourth dimension when falling prices and rise debts conspired against the survival of family farmers, the two political parties seemed incapable of representing the needs of poor farmers. And so brotherhood members organized a political political party—the People's Political party, or the Populists, as they came to exist known. The Populists attracted supporters across the nation by appealing to those convinced that at that place were deep flaws in the political economic system of Gilded Age America, flaws that both political parties refused to address. Veterans of earlier fights for currency reform, disaffected industrial laborers, proponents of the chivalrous socialism of Edward Bellamy'southward popular Looking Astern, and the champions of Henry George's farmer-friendly "unmarried-taxation" proposal joined brotherhood members in the new political party. The Populists nominated former Ceremonious War general James B. Weaver as their presidential candidate at the political party's commencement national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, on July 4, 1892.21

At that meeting the party adopted a platform that crystallized the alliance's cooperate programme into a coherent political vision. The platform's preamble, written past longtime political iconoclast and Minnesota populist Ignatius Donnelly, warned that "the fruits of the toil of millions [had been] boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few."22 Taken as a whole, the Omaha Platform and the larger Populist motion sought to counter the scale and power of monopolistic commercialism with a strong, engaged, and modern federal government. The platform proposed an unprecedented expansion of federal power. It advocated nationalizing the country's railroad and telegraph systems to ensure that essential services would be run in the best interests of the people. In an attempt to bargain with the lack of currency available to farmers, it advocated postal savings banks to protect depositors and extend credit. Information technology called for the institution of a network of federally managed warehouses—called subtreasuries—which would extend government loans to farmers who stored crops in the warehouses as they awaited higher market prices. To relieve debtors it promoted an inflationary budgetary policy by monetizing silverish. Direct ballot of senators and the secret ballot would ensure that this federal government would serve the interest of the people rather than entrenched partisan interests, and a graduated income tax would protect Americans from the establishment of an American aristocracy. Combined, these efforts would, Populists believed, help shift economical and political power dorsum toward the nation's producing classes.

In the Populists' first national ballot entrada in 1892, Weaver received over ane one thousand thousand votes (and twenty-two balloter votes), a truly startling performance that signaled a bright hereafter for the Populists. And when the Panic of 1893 sparked the worst economic depression the nation had ever even so seen, the Populist motility won further credibility and gained fifty-fifty more footing. Kansas Populist Mary Lease, one of the motion's most fervent speakers, famously, and perhaps apocryphally, called on farmers to "raise less corn and more than Hell." Populist stump speakers crossed the state, speaking with righteous indignation, blaming the greed of business elites and corrupt party politicians for causing the crunch fueling America's widening inequality. Southern orators like Texas'south James "Cyclone" Davis and Georgian firebrand Tom Watson stumped across the South decrying the abuses of northern capitalists and the Democratic Political party. Pamphlets such equally Westward. H. Harvey's Coin'due south Financial School and Henry D. Lloyd's Wealth Against Commonwealth provided Populist answers to the age'due south many perceived problems. The faltering economy combined with the Populist'southward extensive organizing. In the 1894 elections, Populists elected six senators and seven representatives to Congress. The third party seemed destined to conquer American politics.23

The movement, withal, still faced substantial obstacles, specially in the South. The failure of alliance-backed Democrats to alive up to their campaign promises drove some southerners to break with the party of their forefathers and join the Populists. Many, notwithstanding, were unwilling to take what was, for southerners, a radical step. Southern Democrats, for their part, responded to the Populist challenge with electoral fraud and racial demagoguery. Both severely express Populist gains. The alliance struggled to rest the pervasive white supremacy of the American South with their call for a grand spousal relationship of the producing class. American racial attitudes—and their virulent southern strain—simply proved besides formidable. Democrats race-baited Populists, and Populists capitulated. The Colored Farmers' Brotherhood, which had formed as a segregated sister organisation to the southern alliance and had as many as 250,000 members at its elevation, fell casualty to racial and class-based hostility. The group went into rapid decline in 1891 when faced with the violent white repression of a number of Colored Farmers' Alliance–sponsored cotton picker strikes. Racial mistrust and partition remained the rule, fifty-fifty amidst Populists, and fifty-fifty in Due north Carolina, where a political wedlock of convenience between Populists and Republicans–fusion–resulted in the ballot of Populist Marion Butler to the Senate. Populists opposed Autonomous corruption, merely this did non necessarily make them champions of interracial democracy. As Butler explained to an audience in Edgecombe County, "We are in favor of white supremacy, just we are not in favor of cheating and fraud to get it."

By the middle of the 1890s, Populism had exploded in popularity. The outset major political force to tap into the vast discomfort of many Americans with the disruptions wrought by industrial commercialism, the Populist Party seemed poised to capture political victory. And all the same, even as Populism gained national traction, the movement was stumbling. The party's frequently divided leadership establish it difficult to shepherd what remained a diverse and loosely organized coalition of reformers toward unified political activeness. The Omaha platform was a radical document, and some land party leaders selectively embraced its reforms. More importantly, the institutionalized parties were still as well potent, and the Democrats loomed, ready to swallow Populist frustrations and inaugurate a new era of American politics.

VI. William Jennings Bryan and the Politics of Gold

William Jennings Bryan, 1896. Library of Congress, LC-USZC2-6259.

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860–July 26, 1925) accomplished many unlike things in his life: he was a skilled orator, a Nebraska congressman, a three-fourth dimension presidential candidate, U.Due south. secretary of country nether Woodrow Wilson, and a lawyer who supported prohibition and opposed Darwinism (virtually notably in the 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial). In terms of his political career, he won national renown for his attack on the gold standard and his tireless promotion of costless argent and policies for the benefit of the boilerplate American. Although Bryan was unsuccessful in winning the presidency, he forever altered the course of American political history.24

Bryan was born in Salem, Illinois, in 1860 to a devout family unit with a potent passion for police, politics, and public speaking. At twenty, he attended Union Constabulary College in Chicago and passed the bar before long thereafter. After his marriage to Mary Baird in Illinois, Bryan and his young family relocated to Nebraska, where he won a reputation amidst the state's Autonomous Party leaders every bit an extraordinary orator. Bryan later won recognition equally one of the greatest speakers in American history.

When economical depressions struck the Midwest in the late 1880s, despairing farmers faced low crop prices and plant few politicians on their side. While many rallied to the Populist cause, Bryan worked from within the Democratic Political party, using the strength of his oratory. Later delivering ane speech communication, he told his married woman, "Terminal night I found that I had a ability over the audience. I could move them as I chose. I have more than usual power as a speaker. . . . God grant that I may use information technology wisely."25He soon won ballot to the Firm of Representatives, where he served for two terms. Although he lost a bid to bring together the Senate, Bryan turned his attention to a higher position: the presidency of the U.s.. There, he believed he could modify the country past defending farmers and urban laborers against the corruptions of large business.

In 1895–1896, Bryan launched a national speaking tour in which he promoted the free coinage of silver. He believed that bimetallism, by inflating American currency, could alleviate farmers' debts. In dissimilarity, Republicans championed the gold standard and a flat coin supply. American monetary standards became a leading entrada issue. And then, in July 1896, the Democratic Party's national convention met to choose their presidential nominee in the upcoming election. The political party platform asserted that the gold standard was "non only un-American but anti-American." Bryan spoke concluding at the convention. He astounded his listeners. At the conclusion of his stirring oral communication, he alleged, "Having behind united states of america the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cantankerous of gold."26 After a few seconds of stunned silence, the convention went wild. Some wept, many shouted, and the band began to play "For He's a Jolly Proficient Fellow." Bryan received the 1896 Democratic presidential nomination.

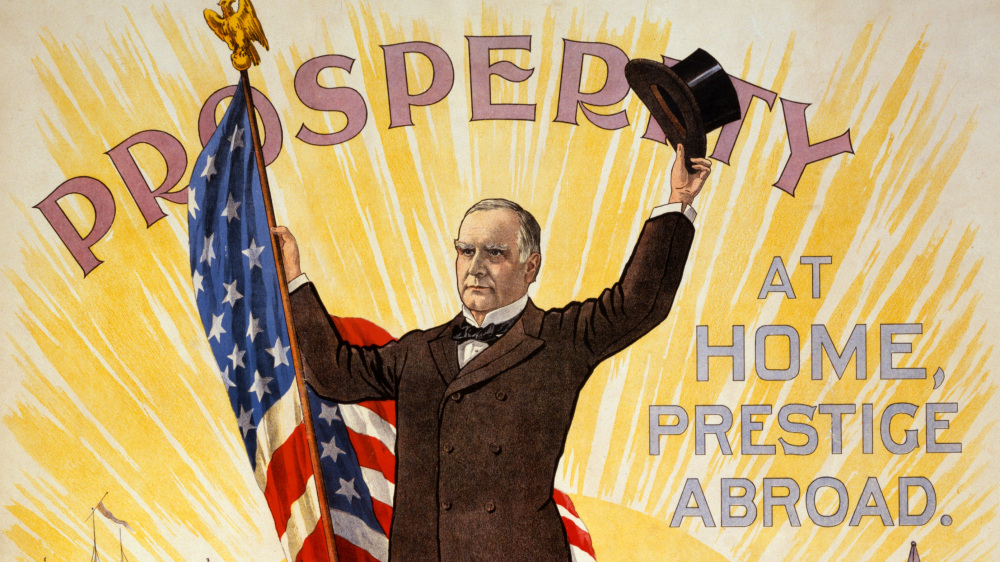

The Republicans ran William McKinley, an economical conservative who championed business organization interests and the aureate standard. Bryan crisscrossed the country spreading the silver gospel. The election drew enormous attention and much emotion. According to Bryan'due south wife, he received two g messages of support every day that year, an enormous amount for any politician, let lonely one not currently in function. Notwithstanding Bryan could non defeat McKinley. The pro-concern Republicans outspent Bryan'south campaign fivefold. A notably high 79.3 percentage of eligible American voters cast ballots, and turnout averaged 90 percent in areas supportive of Bryan, merely Republicans swayed the population-dense Northeast and Great Lakes region and stymied the Democrats.27

In early on 1900, Congress passed the Gilded Standard Act, which put the country on the gold standard, effectively ending the argue over the nation's monetary policy. Bryan sought the presidency over again in 1900 just was again defeated, as he would exist all the same over again in 1908.

Conservative William McKinley promised prosperity to ordinary Americans through his "audio money" initiative, a policy he ran on during his ballot campaigns in 1896 and again in 1900. This election poster touts McKinley'southward gold standard policy every bit bringing "Prosperity at Home, Prestige Abroad." "Prosperity at dwelling, prestige abroad," [between 1895 and 1900]. Library of Congress,.

Bryan was among the most influential losers in American political history. When the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party nominated the Nebraska congressman in 1896, Bryan'southward fiery condemnation of northeastern financial interests and his impassioned calls for "free and unlimited coinage of silvery" co-opted popular Populist bug. The Democrats stood fix to siphon off a large proportion of the Populists' political back up. When the People'southward Party held its own convention two weeks afterwards, the party's moderate wing, in a fiercely contested move, overrode the objections of more ideologically pure Populists and nominated Bryan every bit the Populist candidate as well. This strategy of temporary "fusion" movement fatally fractured the motility and the party. Populist energy moved from the radical-however-notwithstanding-weak People's Party to the more moderate-nonetheless-powerful Autonomous Party. And although at first glance the Populist motion appears to have been a failure—its small-scale electoral gains were short-lived, it did little to dislodge the entrenched 2-party arrangement, and the Populist dream of a cooperative democracy never took shape—in terms of lasting impact, the Populist Party proved the most significant third-party movement in American history. The agrarian revolt established the roots of afterward reform, and the bulk of policies outlined inside the Omaha Platform would eventually be put into law over the following decades under the management of center-class reformers. In large measure, the Populist vision laid the intellectual groundwork for the coming progressive motility.28

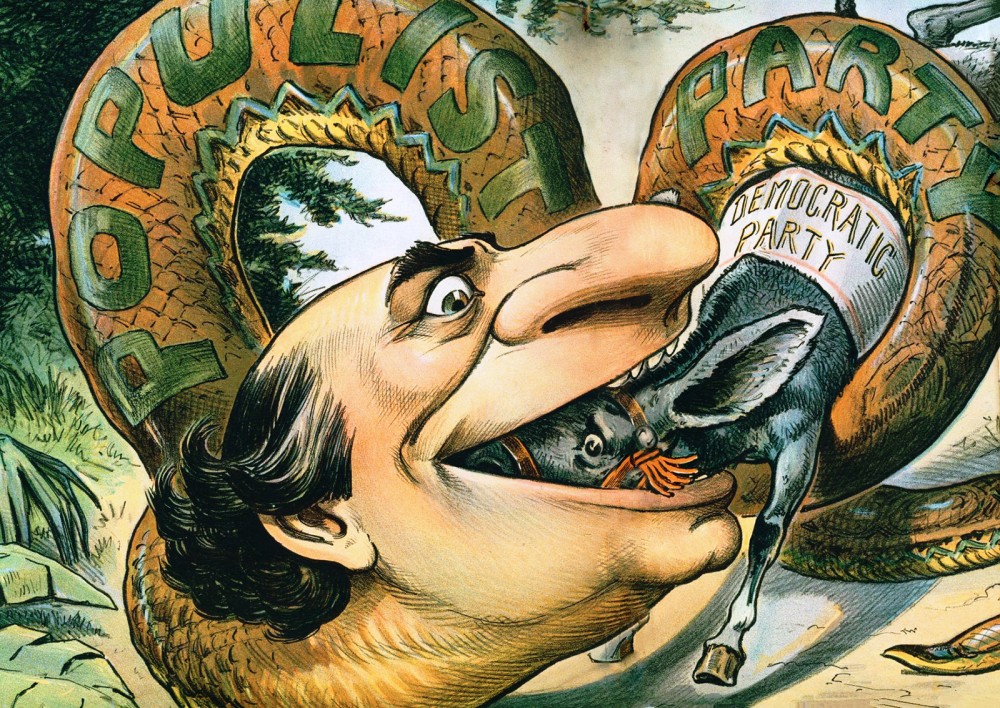

William Jennings Bryan espoused Populist politics while working inside the two-party organisation as a Democrat. Republicans characterized this as a kind hijacking by Bryan, arguing that the Democratic Party was now a party of a radical faction of Populists. The pro-Republican mag Judge rendered this perspective in a political cartoon showing Bryan (representing Populism writ large) as a huge serpent swallowing a bucking mule (representing the Autonomous party). Political Cartoon, Judge, 1896. Wikimedia.

American socialists carried on the Populists' radical tradition past uniting farmers and workers in a sustained, decades-long political struggle to reorder American economic life. Socialists argued that wealth and power were consolidated in the hands of besides few individuals, that monopolies and trusts controlled also much of the economy, and that owners and investors grew rich while the workers who produced their wealth, despite massive productivity gains and rising national wealth, withal suffered from low pay, long hours, and unsafe working weather. Karl Marx had described the new industrial economic system every bit a worldwide form struggle between the wealthy bourgeoisie, who owned the means of production, such every bit factories and farms, and the proletariat, factory workers and tenant farmers who worked only for the wealth of others. According to Eugene Debs, socialists sought "the overthrow of the capitalist system and the emancipation of the working class from wage slavery."29 Under an imagined socialist cooperative commonwealth, the means of production would be owned collectively, ensuring that all men and women received a fair wage for their labor. Co-ordinate to socialist organizer and newspaper editor Oscar Ameringer, socialists wanted "buying of the trust by the regime, and the ownership of the government by the people."xxx

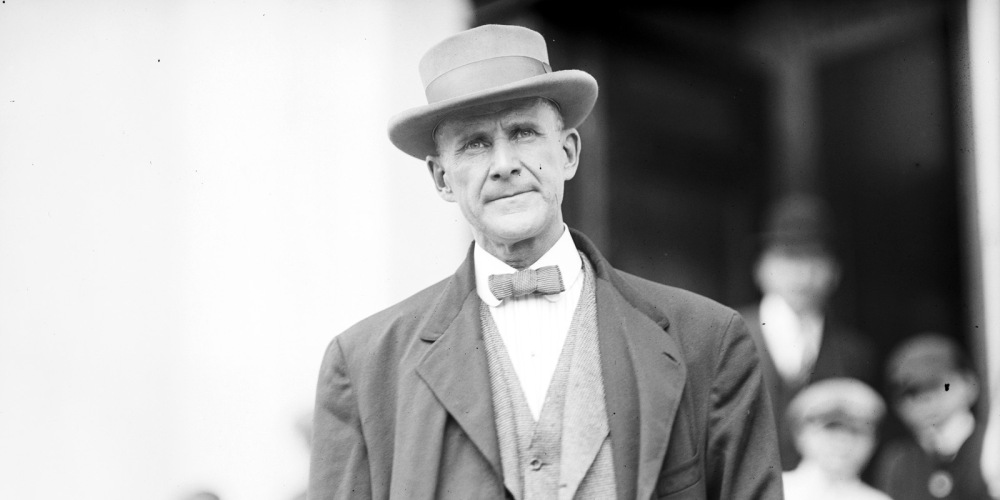

American socialist leader Eugene Victor Debs, 1912. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-hec-01584.

The socialist movement drew from a various constituency. Party membership was open up to all regardless of race, gender, class, ethnicity, or religion. Many prominent Americans, such as Helen Keller, Upton Sinclair, and Jack London, became socialists. They were joined by masses of American laborers from across the The states: factory workers, miners, railroad builders, tenant farmers, and small farmers all united under the scarlet flag of socialism. Many united with labor leader William D. "Big Bill" Haywood and other radicals in 1905 to class the Industrial Workers of the Globe (IWW), the "Wobblies," a radical and confrontational union that welcomed all workers, regardless of race or gender.31 Others turned to politics.

The Socialist Political party of America (SPA), founded in 1901, carried on the American tertiary-party political tradition. Socialist mayors were elected in thirty-3 cities and towns, from Berkeley, California, to Schenectady, New York, and two socialists—Victor Berger from Wisconsin and Meyer London from New York—won congressional seats. All told, over i yard socialist candidates won various American political offices. Julius A. Wayland, editor of the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, proclaimed that "socialism is coming. It'south coming like a prairie fire and naught tin end information technology . . . you tin can experience information technology in the air."32 By 1913 at that place were 150,000 members of the Socialist Party and, in 1912, Eugene V. Debs, the Indiana-born Socialist Party candidate for president, received nearly one million votes, or 6 percent of the full.33

Over the following years, nonetheless, the embrace of many socialist policies by progressive reformers, internal ideological and tactical disagreements, a failure to dissuade most Americans of the perceived incompatibility between socialism and American values, and, especially, government oppression and censorship, particularly during and after World War I, ultimately sank the party. Like the Populists, all the same, socialists had tapped into a deep well of discontent, and their energy and organizing filtered out into American civilisation and American politics.

8. Conclusion

The march of uppercase transformed patterns of American life. While some enjoyed unprecedented levels of wealth, and an always-growing piece of middle-class workers won an ever more comfortable standard of living, vast numbers of farmers lost their land and a growing industrial working class struggled to earn wages sufficient to support themselves and their families. Industrial commercialism brought wealth and information technology brought poverty; it created owners and investors and it created employees. Merely whether winners or losers in the new economy, all Americans reckoned in some way with their new industrial earth.

Nine. Primary Sources

1. William Graham Sumner on Social Darwnism (ca.1880s)

William Graham Sumner, a sociologist at Yale Academy, penned several pieces associated with the philosophy of Social Darwinism. In the post-obit, Sumner explains his vision of nature and liberty in a only social club.

two. Henry George,Progress and Poverty,Selections (1879)

In 1879, the economist Henry George penned a massive bestseller exploring the contradictory ascension of both rapid economic growth and crippling poverty.

3. Andrew Carnegie's Gospel of Wealth (1889)

Andrew Carnegie, the American steel titan, explains his vision for the proper function of wealth in American society.

4. Grover Cleveland's Veto of the Texas Seed Bill (1887)

Among a crushing drought that devastated many Texas farmers, Grover Cleveland vetoed a nib designed to help farmers recover past supplying them with seed. In his veto bulletin, Cleveland explained his vision of proper government.

5. The "Omaha Platform" of the People's Party (1892)

In 1892, the People's, or Populist, Party crafted a platform that indicted the corruptions of the Gilded Age and promised authorities policies to aid "the people."

6. Dispatch from a Mississippi Colored Farmers' Alliance (1889)

The Colored Farmers' Brotherhood, an African American alternative to the whites-only Southern Farmers' Brotherhood, organized as many as a meg Blackness southerners against the injustices of the predominately cotton wool-based, southern agronomical economy. Black Populists, however, were always more vulnerable to the violence of white southern conservatives than their white counterparts. Here, the publicationThe Forumpublishes an account of violence confronting Black Populists in Mississippi.

7. Lucy Parsons on Women and Revolutionary Socialism (1905)

Lucy Parsons was born into slavery in Texas, married a white radical, Albert Parsons, and moved to Chicago where they both worked on behalf of radical causes. After Albert Parsons was executed for conspiracy in the backwash of the Haymarket bombing, Lucy Parsons emerged as a major American radical and vocal advocate of riot. In 1905, she spoke before the founding convention of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

8. "The Tournament of Today" (1883)

"Print shows a jousting tournament between an oversized knight riding horse-shaped armor labeled "Monopoly" over a locomotive, with a long feather labeled "Arrogance", and carrying a shield labeled "Abuse of the Legislature" and a lance labeled "Subsidized Printing", and a barefoot human labeled "Labor" riding an emaciated equus caballus labeled "Poverty", and carrying a sledgehammer labeled "Strike". On the left is seating "Reserved for Capitalists" where Cyrus W. Field, William H. Vanderbilt, John Roach, Jay Gould, and Russell Sage are sitting. On the right, behind the labor section, are telegraph lines flight monopoly banners that are labeled "Wall St., W.U.T. Co., [and] N.Y.C. RR"."

9. Lawrence Textile Strike (1912)

In 1912, The Industrial Workers of the Earth (the IWW, or the "Wobblies") organized textile workers in Lawrence and Lowell, Massachusetts. This photo shows strikers, carrying American flags, confronting strikebreakers and militia bayonets.

X. Reference Material

This chapter was edited by Joseph Locke, with content contributions past Andrew C. Baker, Nicholas Claret, Justin Clark, Dan Du, Caroline Bunnell Harris, David Hochfelder Scott Libson, Joseph Locke, Leah Richier, Matthew Simmons, Kate Sohasky, Joseph Super, and Kaylynn Washnock.

Recommended citation: Andrew C. Baker et al., "Capital and Labor," Joseph Locke, ed., in The American Yawp, eds. Joseph Locke and Ben Wright (Stanford, CA: Stanford Academy Press, 2018).

Recommended Reading

- Beckert, Sven. Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896. Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Cambridge Academy Press, 2001.

- Benson, Susan Porter. Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890–1940. Champaign: University of Illinois Printing, 1986.

- Cameron, Ardis. Radicals of the Worst Sort: Laboring Women in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1860–1912. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Chambers, John W. The Tyranny of Change: America in the Progressive Era, 1890–1920, 2nd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

- Chandler, Alfred D., Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business organization. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Printing, 1977.

- Chandler, Alfred D., Jr. Calibration and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Cronon, William. Nature's Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: Norton, 1991.

- Edwards, Rebecca. New Spirits: Americans in the Gold Age, 1865–1905. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Enstad, Nan. Ladies of Labor, Girls of Risk: Working Women, Popular Civilisation, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Columbia University Printing, 1999.

- Fink, Leon. Workingmen's Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics. Chicago: Academy of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Goodwyn, Lawrence. Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- Green, James. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the Get-go Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Aureate Age America. New York City: Pantheon Books, 2006.

- Greene, Julie. Pure and Simple Politics: The American Federation of Labor and Political Activism, 1881–1917. New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 1998.

- Hofstadter, Richard. Social Darwinism in American Thought. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944.

- Johnson, Kimberley S. Governing the American Land: Congress and the New Federalism, 1877–1929. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Press, 2006.

- Kazin, Michael. A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. New York: Knopf, 2006.

- Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Krause, Paul. The Boxing for Homestead, 1880–1892: Politics, Civilisation, and Steel. Pittsburgh, PA: Academy of Pittsburgh Press, 1992.

- Lamoreaux, Naomi R. The Great Merger Move in American Business, 1895–1904. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- McMath, Robert C., Jr. American Populism: A Social History, 1877–1898. New York: Loma and Wang, 1993.

- Montgomery, David. The Autumn of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865–1925. New York: Cambridge Academy Press, 1988.

- Painter, Nell Irvin. Continuing at Armageddon: The United States, 1877–1919. New York: Norton, 1987.

- Postel, Charles. The Populist Vision. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Sanders, Elizabeth. Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

- Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Golden Age. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

End Notes

- David T. Burbank, Reign of the Rabble: The St. Louis General Strike of 1877 (New York: Kelley, 1966), xi. [↩]

- Robert Five. Bruce, 1877: Yr of Violence (New York: Dee, 1957); Philip S. Foner, The Cracking Labor Uprising of 1877 (New York: Monad Press, 1977); David Omar Stowell, ed., The Great Strikes of 1877 (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008). [↩]

- Alfred D. Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1977); David A. Hounshell, From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984). [↩]

- Hounshell, From the American Organisation, 153–188. [↩]

- Alfred D. Chandler Jr., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Printing, 1990), 52. [↩]

- Chandler, Visible Mitt. [↩]

- Naomi R. Lamoreaux, The Not bad Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904 (New York: Cambridge University Printing, 1985). [↩]

- Come across particularly Run into especially Edward O'Donnell, Henry George and the Crunch of Inequality: Progress and Poverty in the Gilded Historic period (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 41–45. [↩]

- Michael McGerr, A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Motion in America, 1870–1920 (New York: Free Press, 2003). [↩]

- Richard Hofstadter, Social Darwinism in American Thought (Boston: Beacon Books, 1955). [↩]

- Henry Louis Mencken, The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (Boston: Luce, 1908), 102–103. [↩]

- William Graham Sumner, Earth-Hunger, and Other Essays, ed. Albert Galloway Keller (New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Press, 1913), 234. [↩]

- Leon Fink, Workingmen's Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics (Urbana: University of Illinois Printing, 1983). [↩]

- Ruth A. Allen, The Great Southwest Strike (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1942). [↩]

- James R. Green, Decease in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Move and the Bombing That Divided Gilded Age America. New York: Pantheon Books, 2006). [↩]

- Paul Krause, The Battle for Homestead, 1890–1892: Politics, Civilization, and Steel (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992). [↩]

- Almont Lindsey, The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and of a Great Labor Upheaval (Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing, 1943). [↩]

- Historians of the Populists have produced a large number of excellent histories. See especially Lawrence Goodwyn, Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976); and Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (New York: Oxford Academy Press, 2009). [↩]

- Lawrence Goodwyn argued that the Populists' "cooperative vision" was the central element in their hopes of a "autonomous economy." Goodwyn, Democratic Hope, 54. [↩]

- John Donald Hicks, The Populist Defection: A History of the Farmers' Alliance and the People's Political party (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1931), 178. [↩]

- Ibid., 236. [↩]

- Edward McPherson, A Handbook of Politics for 1892 (Washington, DC: Chapman, 1892), 269. [↩]

- Hicks, Populist Defection, 321–339. [↩]

- For William Jennings Bryan, see especially Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Knopf, 2006). [↩]

- Ibid., 25. [↩]

- Richard Franklin Bensel, Passion and Preferences: William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Democratic Convention (Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Cambridge University Printing, 2008), 232. [↩]

- Lyn Ragsdale, Vital Statistics on the Presidency (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press, 1998), 132–138. [↩]

- Elizabeth Sanders, The Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers, and the American State, 1877–1917 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). [↩]

- Eugene V. Debs, "The Socialist Party and the Working Grade," International Socialist Review (September 1904). [↩]

- Oscar Ameringer, Socialism: What Information technology Is and How to Get It (Milwaukee, WI: Political Activity, 1911), 31. [↩]

- Philip Due south. Foner, The Industrial Workers of the World 1905–1917 (New York: International Publishers, 1965. [↩]

- R. Laurence Moore, European Socialists and the American Promised Country (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 214. [↩]

- Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs, Citizen and Socialist (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1983). [↩]

mcclemensaness1936.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.americanyawp.com/text/16-capital-and-labor/

0 Response to "Vanderbilt Monopoly to the Point That Laws Were Enacted to Keep His Practices From Happening Again"

Post a Comment